Two travel albums of Egypt from the collection of Georgiana Goddard King

were recently cataloged (2012.8.1.a-xx, and 2012.8.2.a-xx). They include amazing photographs of people and sites by Pascal Sebah and Antonio Beato and will be used in a GSEM course later this Spring.

were recently cataloged (2012.8.1.a-xx, and 2012.8.2.a-xx). They include amazing photographs of people and sites by Pascal Sebah and Antonio Beato and will be used in a GSEM course later this Spring.

Category Archives: Archaeology Collections

Peruvian Textiles – Update

Our first Collections Information Management intern lives to tell the tale!

Classics graduate student Diane Amoroso-O’Connor has been working for the past academic year as our Collections Information Management Intern. This position allowed her to experience all facets of working with collections information – from individual object cataloging to global data management in the new EmbARK database.

Of her work on the new Art and Artifact Collections database, Diane writes:

As the Collections Information Management Intern, I split my time between small-scale research projects, in which I research items from our collection that need a little more information, and large-scale data projects, in which I might edit a few thousand records at a time. Fortunately, the same general principles of data organization apply to both; the smaller projects provide practice for the larger data concerns, and the larger projects provide the global view of the collections that informs good object entries.

My first task in Collections was to accession a group of nine coins, and then to edit or add to all of our other coin entries, aiming for consistency and clarity. In order to identify the coins, I used the standard sources as references in the Collections (The Roman Imperial Coinage, etc.) but also tested out a variety of online sources, both academic and commercial. This gave me a look at the ways sites organized information and created something word-searchable out of graphic or image-based data. After entering the new data, I worked on the old data, editing for uniformity across the collection and (hopefully!) reducing ambiguities in titles or descriptions, such as whether a “Roman Coin” was issued in the Roman period, issued by the Roman government, or issued in Rome.

These sorts of changes were needed throughout the database, so I’ve gone through fictile ivories, geological photographs, anthropological artifacts, and all sorts of objects to make sure that data like dates or geographic origins of items are presented consistently across the database. Taking the objects in groups of thousands actually helps here; I can easily insure that I’m using the same terms or formatting throughout a type of item, then several types of items, building up to the database level.

Among the clean-up tasks, I’ve been able to intersperse research on our Egyptian Collections. Some of my favorite items in the College Collections are our pieces of Egyptian Predynastic pottery, donated by the American Exploration Society. In addition to checking the database entries against the two sets of cards for the objects, and updating some of the terminology used in the database, I had the opportunity to photograph these items (using a camera far better than any I could be trusted to own). Filling in lost data on our ushabtis has been my other pet project. I used Schneider’s typology to date our ushabtis, what I liked to call the “Hair and Handbag System,” as wigs and bags molded, carved, or painted on the figurines provided some of the most useful diagnostic data. This also allowed me to use Schneider’s terminology to make our descriptions uniform and easily referenced in Schneider’s work for anyone researching these objects in the future.

(If you don’t see an image below, it means that you will need to download the Quicktime plugin for your web browser).

Above: Egyptian Faience Ushabti (Funerary Sculpture) [F.164]

Of late, my large projects have moved from the editing and reformatting of data to the classification of objects. We’re working with a few different hierarchical systems that should allow users to browse the Collections. I’ve been classifying the types of objects by using The Revised Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging: A Revised and Expanded Version of Robert G. Chenhall’s System for Classifying Man-Made Objects, as well adding keywords to use a hierarchical system based on materials, time periods, subjects, and other features, grounded in The Getty’s Art and Architecture Thesaurus. While neither system captures every object or subject perfectly, either one provides a powerful search tool for anyone doing research on the collection, even before making any modifications or additions to the systems. (As a related note, if anyone has ever wanted to research numismatic depictions of helmets, it would be a very fruitful keyword search at the moment.)

Throughout this year, I’ve been amazed to see what the Collections database has become, and the research that other students have already put into action. Most of all, I’ve been fortunate to help make Collections a better tool for research and teaching, as well as work with, and learn from, Cheryl, Marianne, and Emily.

Better know the collections: Terracottas

Andrea Guzzetti is a seventh-year graduate student in the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology. He is working with the Art and Artifact Collections as part of an NEH Curatorial Internship, which gives graduate students in the Graduate Group in Archaeology, Classics, and History of Art the opportunity to spend a semester (or summer) working with collections at Bryn Mawr and a second semester carrying out a project at a partner institution in the Philadelphia area.

Here is what Andrea has been working on this semester:

In particular, my work in the Collections revolves around a group of ca. 300 terracotta figurines, mostly Greek and Roman. The majority of them were given to the College by Bryn Mawr alumnae or faculty members. Since they have been acquired at different times and under different circumstances, the information available on them varies widely in quantity and quality. A few pieces have been published in journals or exhibition catalogues, such as a trio of Etruscan heads (T.7-9) and a weight with an owl in relief (T.182), while several others have been discussed in senior theses or class papers. More often, however, all that is known about these artifacts is limited to the contents of the old catalog cards, which can range from a detailed description and list of comparanda to a generic title (“terracotta head”) and measurements.

My primary task, then, has been to check the existing data, which had been transferred to the new Collections database, and to update and expand it. More specifically, the main goal of the project was to provide each object with a minimum of standardized information (title, description, measurements, date) that could be employed for display labels and online searches. Once the work had progressed enough, I began gathering further details about the iconography and the possible function of as many artifacts as possible.

The majority of the terracottas represent human figures, especially seated or standing females, although the subjects can sometimes be identified as deities. The figures are usually alone; in some cases there are couples or women with children (T.83).

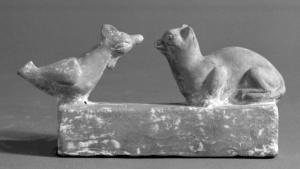

The collection also includes several animal figurines (T.125) and reproductions of body parts such as eyes or feet (T.97, T.192); the latter probably constitute offerings presented to healing sanctuaries in thanksgiving for the recovery of the corresponding organ. The artifacts range in date from the Late Geometric period (late eighth-early seventh century BCE) to Roman Imperial times.

A general problem encountered during the project is the lack of context for practically all the terracottas. Since many objects are fragmentary or quite worn, or both, it is difficult to study them on the basis of style alone. Sometimes the region or site where an artifact was found is known, or can be determined from archival information on the donor, but such knowledge is seldom useful, as in the case of surface finds. Ignorance about their origin also raises questions of authenticity. For example, some of the best preserved figurines, which resemble popular Hellenistic types known from such sites as Tanagra in Boeotia or Myrina in Asia Minor, exhibit technical and iconographical features that suggest they are modern creations, produced to satisfy the demand for this kind of object that developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, following the discovery of the first figurines (T.77).

(If you don’t see an image below, it means that you will need to download the Quicktime plugin for your web browser).

Above: Terracotta figurine of a seated woman (T.77)

Nevertheless, the collection itself, including the possible fakes, constitutes a very valuable tool for research and teaching, given the variety of techniques and styles represented in it, and I have really enjoyed working on this material. Although I have some experience with museum cataloging, I had never had the opportunity to work with terracottas before, and I have learned much about this class of artifacts.

Better know the collections: Cataloging sherds excavated at Tarsus

Holly Pritchett is a graduate student in archaeology who has been cataloging pottery sherds from an excavation at Gözlükule, Tarsus, Turkey since the beginning of the 2009-10 academic year. To date, she has photographed and created descriptive records for over 800 sherds.

Here’s what Holly has to say about her project:

Gözlükule is the name of the mound south of the modern city of Tarsus on which the ancient settlement was located. Excavations carried out at Gözlükule show that it was first settled in the Late Neolithic Period, approximately 7000 BCE. Tarsus is situated on the Cydnos River just a few miles from the Mediterranean Sea. In ancient times it was strategically positioned at the junction of important roads of the time. Its location is one of the main factors for its long history, which wasn’t always entirely peaceful. During the 2nd millennium BCE, Tarsus was controlled by the Hittites. In the 9th century BCE, the Assyrians ruled Tarsus and in 612 BCE, the Persians attacked the city. The Persians were still in control when Alexander the Great visited in 333 BCE. After the death of Alexander, Tarsus was briefly held by the Egyptian Ptolemies and then by Rome. Julius Caesar visited the city in 47 BCE and after Caesar’s death, Marc Antony met Cleopatra in Tarsus (41 BCE) to plan their ill-fated revolt against Augustus and Rome.

In 1935, an American archaeological team under the direction of Hetty Goldman began excavations at Gözlükule. Ms. Goldman, Bryn Mawr College Class of 1903, received her Ph.D. from Princeton. This excavation lasted until 1939, when the dig had to be suspended due to the outbreak of World War II. In 1947, Ms. Goldman resumed excavations, which lasted until 1949. As a result of her excavations, 33 levels of habitation were determined, ranging from the Late Neolithic to the Islamic Periods.

It is the sherds from the earlier excavation that I catalogue. Each sherd is assigned an accession number, its dimensions are measured, and the color of the clay is determined by comparing the sherd to a spectrum of colors, referred to as its Munsell color (named after the man who developed the system). This information, along with a brief description is entered into the EmbARK collections database. I also take photographs of every pottery sherd, so a nice close-up picture accompanies each record.

Holly photographing sherds on the copystand.

In my research, I have referred to some of the many day-books written by the archaeological team leader, which contain notes about each day’s excavation, the items found, and drawings. Many of the sherds have been published in the second part of a six-volume set. The entire set includes not only the pottery found at Tarsus, but also the statues, sculptures, and coins that were excavated. Any bibliographic information is also added into the sherd’s database record.

Another one of my interests is ancient fingerprints that sometimes were inadvertently left on clay tablets and pottery when they were first made. Although I have discovered only one fingerprint so far, I examine each sherd, hoping to find a personal testimonial of the potter and/or painter who shaped and decorated these ancient pieces of pottery.