Holly Pritchett is a graduate student in archaeology who has been cataloging pottery sherds from an excavation at Gözlükule, Tarsus, Turkey since the beginning of the 2009-10 academic year. To date, she has photographed and created descriptive records for over 800 sherds.

Here’s what Holly has to say about her project:

Gözlükule is the name of the mound south of the modern city of Tarsus on which the ancient settlement was located. Excavations carried out at Gözlükule show that it was first settled in the Late Neolithic Period, approximately 7000 BCE. Tarsus is situated on the Cydnos River just a few miles from the Mediterranean Sea. In ancient times it was strategically positioned at the junction of important roads of the time. Its location is one of the main factors for its long history, which wasn’t always entirely peaceful. During the 2nd millennium BCE, Tarsus was controlled by the Hittites. In the 9th century BCE, the Assyrians ruled Tarsus and in 612 BCE, the Persians attacked the city. The Persians were still in control when Alexander the Great visited in 333 BCE. After the death of Alexander, Tarsus was briefly held by the Egyptian Ptolemies and then by Rome. Julius Caesar visited the city in 47 BCE and after Caesar’s death, Marc Antony met Cleopatra in Tarsus (41 BCE) to plan their ill-fated revolt against Augustus and Rome.

In 1935, an American archaeological team under the direction of Hetty Goldman began excavations at Gözlükule. Ms. Goldman, Bryn Mawr College Class of 1903, received her Ph.D. from Princeton. This excavation lasted until 1939, when the dig had to be suspended due to the outbreak of World War II. In 1947, Ms. Goldman resumed excavations, which lasted until 1949. As a result of her excavations, 33 levels of habitation were determined, ranging from the Late Neolithic to the Islamic Periods.

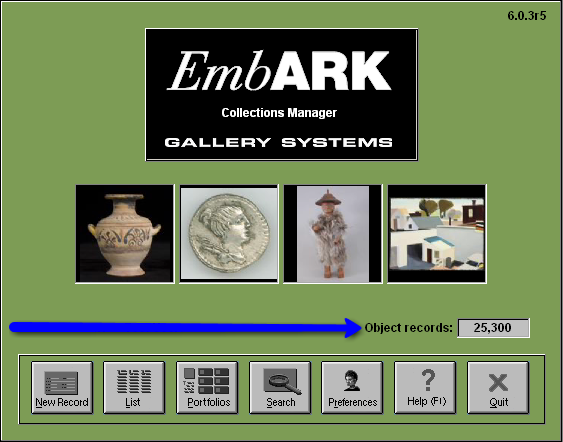

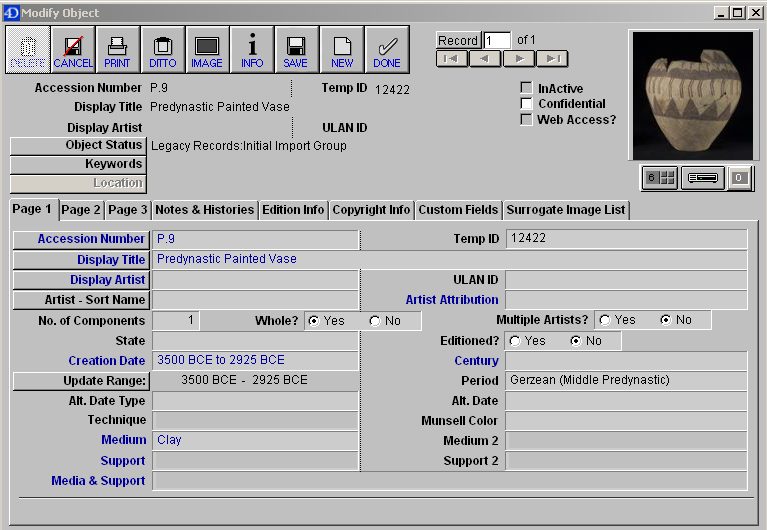

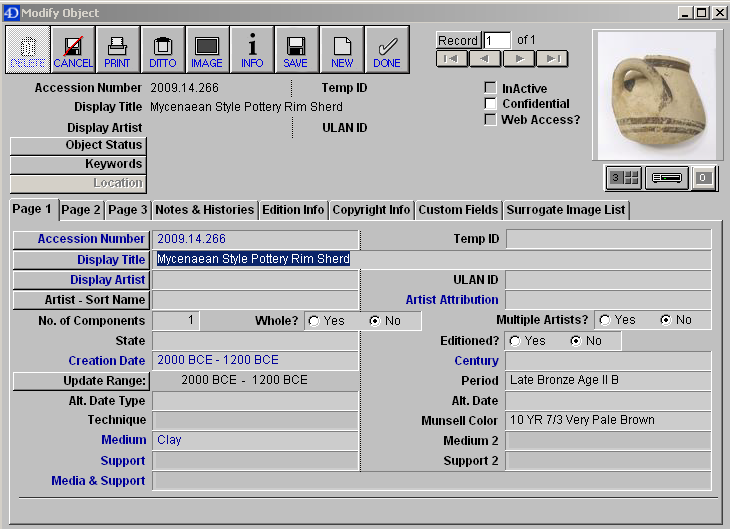

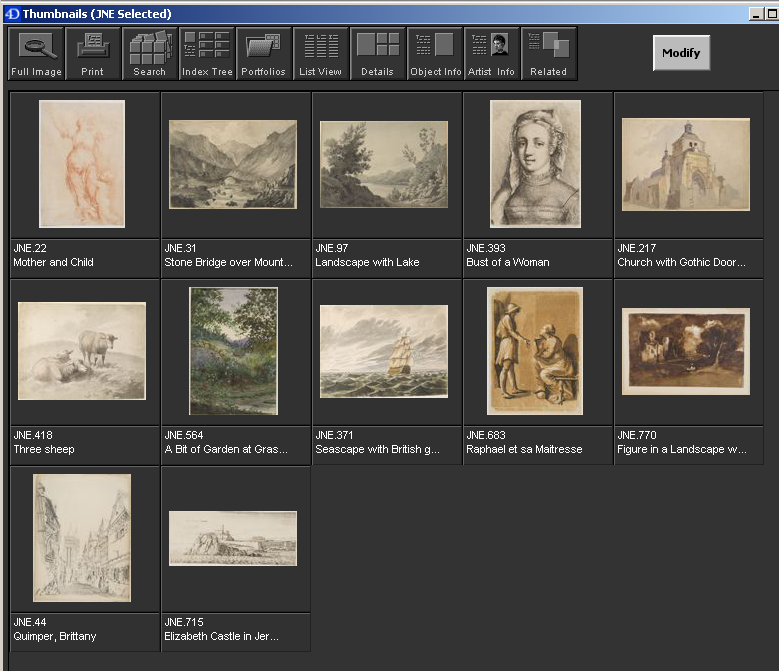

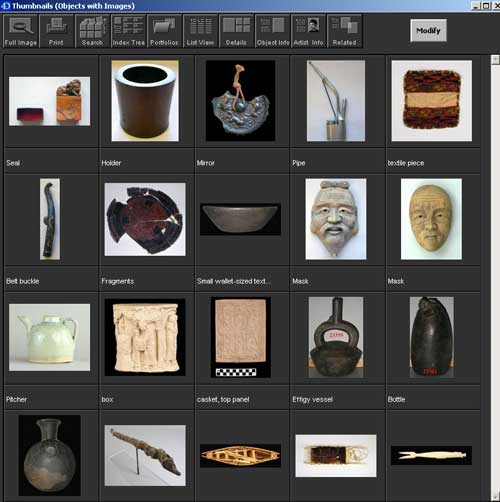

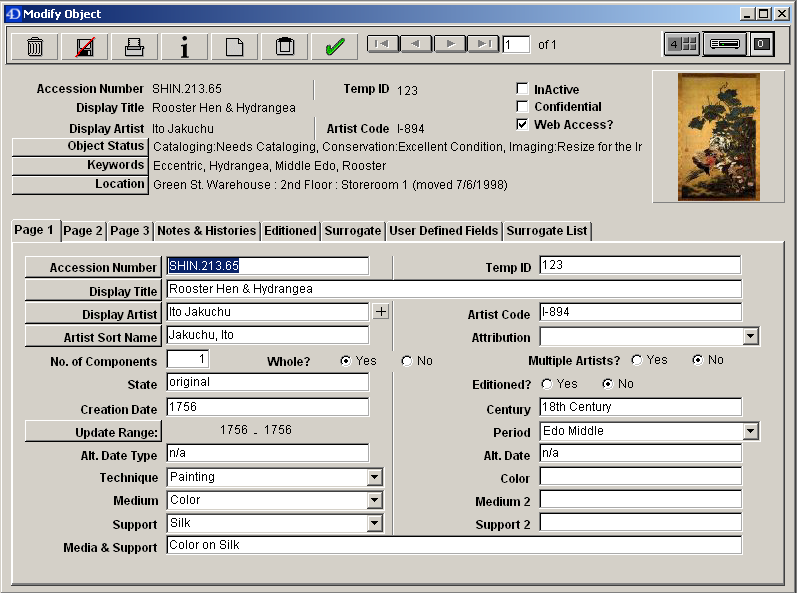

It is the sherds from the earlier excavation that I catalogue. Each sherd is assigned an accession number, its dimensions are measured, and the color of the clay is determined by comparing the sherd to a spectrum of colors, referred to as its Munsell color (named after the man who developed the system). This information, along with a brief description is entered into the EmbARK collections database. I also take photographs of every pottery sherd, so a nice close-up picture accompanies each record.

Holly photographing sherds on the copystand.

In my research, I have referred to some of the many day-books written by the archaeological team leader, which contain notes about each day’s excavation, the items found, and drawings. Many of the sherds have been published in the second part of a six-volume set. The entire set includes not only the pottery found at Tarsus, but also the statues, sculptures, and coins that were excavated. Any bibliographic information is also added into the sherd’s database record.

Another one of my interests is ancient fingerprints that sometimes were inadvertently left on clay tablets and pottery when they were first made. Although I have discovered only one fingerprint so far, I examine each sherd, hoping to find a personal testimonial of the potter and/or painter who shaped and decorated these ancient pieces of pottery.