Andrea Guzzetti is a seventh-year graduate student in the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology. He is working with the Art and Artifact Collections as part of an NEH Curatorial Internship, which gives graduate students in the Graduate Group in Archaeology, Classics, and History of Art the opportunity to spend a semester (or summer) working with collections at Bryn Mawr and a second semester carrying out a project at a partner institution in the Philadelphia area.

Here is what Andrea has been working on this semester:

In particular, my work in the Collections revolves around a group of ca. 300 terracotta figurines, mostly Greek and Roman. The majority of them were given to the College by Bryn Mawr alumnae or faculty members. Since they have been acquired at different times and under different circumstances, the information available on them varies widely in quantity and quality. A few pieces have been published in journals or exhibition catalogues, such as a trio of Etruscan heads (T.7-9) and a weight with an owl in relief (T.182), while several others have been discussed in senior theses or class papers. More often, however, all that is known about these artifacts is limited to the contents of the old catalog cards, which can range from a detailed description and list of comparanda to a generic title (“terracotta head”) and measurements.

My primary task, then, has been to check the existing data, which had been transferred to the new Collections database, and to update and expand it. More specifically, the main goal of the project was to provide each object with a minimum of standardized information (title, description, measurements, date) that could be employed for display labels and online searches. Once the work had progressed enough, I began gathering further details about the iconography and the possible function of as many artifacts as possible.

The majority of the terracottas represent human figures, especially seated or standing females, although the subjects can sometimes be identified as deities. The figures are usually alone; in some cases there are couples or women with children (T.83).

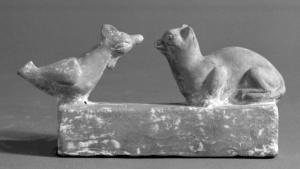

The collection also includes several animal figurines (T.125) and reproductions of body parts such as eyes or feet (T.97, T.192); the latter probably constitute offerings presented to healing sanctuaries in thanksgiving for the recovery of the corresponding organ. The artifacts range in date from the Late Geometric period (late eighth-early seventh century BCE) to Roman Imperial times.

A general problem encountered during the project is the lack of context for practically all the terracottas. Since many objects are fragmentary or quite worn, or both, it is difficult to study them on the basis of style alone. Sometimes the region or site where an artifact was found is known, or can be determined from archival information on the donor, but such knowledge is seldom useful, as in the case of surface finds. Ignorance about their origin also raises questions of authenticity. For example, some of the best preserved figurines, which resemble popular Hellenistic types known from such sites as Tanagra in Boeotia or Myrina in Asia Minor, exhibit technical and iconographical features that suggest they are modern creations, produced to satisfy the demand for this kind of object that developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, following the discovery of the first figurines (T.77).

(If you don’t see an image below, it means that you will need to download the Quicktime plugin for your web browser).

Above: Terracotta figurine of a seated woman (T.77)

Nevertheless, the collection itself, including the possible fakes, constitutes a very valuable tool for research and teaching, given the variety of techniques and styles represented in it, and I have really enjoyed working on this material. Although I have some experience with museum cataloging, I had never had the opportunity to work with terracottas before, and I have learned much about this class of artifacts.