bmc-photography-documentation-june-23-2011

This document is intended to serve as documentation of the photographic procedures we use at Bryn Mawr College, including file naming standards, color correction, and making rotating images.

bmc-photography-documentation-june-23-2011

This document is intended to serve as documentation of the photographic procedures we use at Bryn Mawr College, including file naming standards, color correction, and making rotating images.

Classics graduate student Diane Amoroso-O’Connor has been working for the past academic year as our Collections Information Management Intern. This position allowed her to experience all facets of working with collections information – from individual object cataloging to global data management in the new EmbARK database.

Of her work on the new Art and Artifact Collections database, Diane writes:

As the Collections Information Management Intern, I split my time between small-scale research projects, in which I research items from our collection that need a little more information, and large-scale data projects, in which I might edit a few thousand records at a time. Fortunately, the same general principles of data organization apply to both; the smaller projects provide practice for the larger data concerns, and the larger projects provide the global view of the collections that informs good object entries.

My first task in Collections was to accession a group of nine coins, and then to edit or add to all of our other coin entries, aiming for consistency and clarity. In order to identify the coins, I used the standard sources as references in the Collections (The Roman Imperial Coinage, etc.) but also tested out a variety of online sources, both academic and commercial. This gave me a look at the ways sites organized information and created something word-searchable out of graphic or image-based data. After entering the new data, I worked on the old data, editing for uniformity across the collection and (hopefully!) reducing ambiguities in titles or descriptions, such as whether a “Roman Coin” was issued in the Roman period, issued by the Roman government, or issued in Rome.

These sorts of changes were needed throughout the database, so I’ve gone through fictile ivories, geological photographs, anthropological artifacts, and all sorts of objects to make sure that data like dates or geographic origins of items are presented consistently across the database. Taking the objects in groups of thousands actually helps here; I can easily insure that I’m using the same terms or formatting throughout a type of item, then several types of items, building up to the database level.

Among the clean-up tasks, I’ve been able to intersperse research on our Egyptian Collections. Some of my favorite items in the College Collections are our pieces of Egyptian Predynastic pottery, donated by the American Exploration Society. In addition to checking the database entries against the two sets of cards for the objects, and updating some of the terminology used in the database, I had the opportunity to photograph these items (using a camera far better than any I could be trusted to own). Filling in lost data on our ushabtis has been my other pet project. I used Schneider’s typology to date our ushabtis, what I liked to call the “Hair and Handbag System,” as wigs and bags molded, carved, or painted on the figurines provided some of the most useful diagnostic data. This also allowed me to use Schneider’s terminology to make our descriptions uniform and easily referenced in Schneider’s work for anyone researching these objects in the future.

(If you don’t see an image below, it means that you will need to download the Quicktime plugin for your web browser).

Of late, my large projects have moved from the editing and reformatting of data to the classification of objects. We’re working with a few different hierarchical systems that should allow users to browse the Collections. I’ve been classifying the types of objects by using The Revised Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging: A Revised and Expanded Version of Robert G. Chenhall’s System for Classifying Man-Made Objects, as well adding keywords to use a hierarchical system based on materials, time periods, subjects, and other features, grounded in The Getty’s Art and Architecture Thesaurus. While neither system captures every object or subject perfectly, either one provides a powerful search tool for anyone doing research on the collection, even before making any modifications or additions to the systems. (As a related note, if anyone has ever wanted to research numismatic depictions of helmets, it would be a very fruitful keyword search at the moment.)

Throughout this year, I’ve been amazed to see what the Collections database has become, and the research that other students have already put into action. Most of all, I’ve been fortunate to help make Collections a better tool for research and teaching, as well as work with, and learn from, Cheryl, Marianne, and Emily.

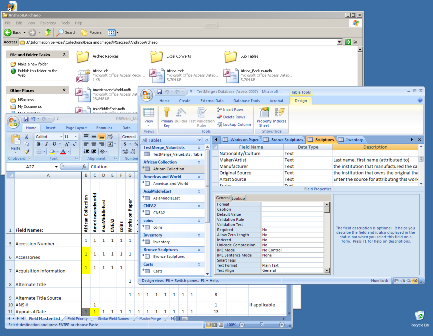

The creation of a comprehensive collections database for Bryn Mawr College’s Art and Artifacts Collections is underway. This extensive, 18-month project is generously funded by the College’s Graduate Group in Archaeology, Classics and History of Art. For the duration of the project, Collections Information Manager Cheryl Klimaszewski (on board as of February 16th) will be assisting collections staff members Emily Croll (Curator and Academic Liaison) and Marianne Weldon (Collections Manager) in the seemingly impossible task of taking 22,000+ records from fourteen different MS Access databases, cleaning them up, and then moving them ever-so-lovingly into EmbARK Collections Manager, a collections information system developed by Gallery Systems. All this, mind you, while also beginning data entry for the additional 40,000 collections objects yet to be cataloged.

This project represents a giant leap forward for the Art and Artifacts Collections. Systems like EmbARK are the way to store information about a collection because they employ relational database technology, which provides structured storage, management, and manipulation of data and allows users to interact with data more effectively. Each record in the database acts as a surrogate for the actual item in the collection, so searching the database means (or in our case, will eventually mean) that users have the collection at their fingertips via the database interface.

The creation of digital images of items in the collection is an essential and ongoing part of this project. To date, over 5000 digital images have been created. Students will continue to photograph objects and to digitize existing photographs and negatives.

An important component of our project is the development of data standards, which will govern how collections data is entered into the system going forward. For instance, will we classify “watercolors” as “paintings” or “works on paper”? This is but one simple example of the types of decisions that must be made as to how we conceptualize our collection, and we plan to make such decisions in consultation with members of the BMC community, as appropriate. Such an effort now will pay off in the end: codifying data standards means that data is entered into the database in an orderly, regular, predictable fashion, which will allow for more efficient and meaningful search capabilities once the collection is available on-line. In addition, the standards we develop at BMC will be based on broader museum standards and best practices. This means that, going forward, our data will be more easily adapted as the broader standards continue to develop and improve, opening up the possibility of collaboration between institutions. The bottom line: spending the time to develop strong data standards now will make the collections more accessible to all users and we will never have to tackle a collections data project on this scale again (well, at least not in our lifetimes).

Reviewing current collections data.

So how does one approach such a monumental task? Cheryl has spent her first two weeks reviewing the current databases to learn the answer to the age old question, “What is really going on here?” Multiple Excel spreadsheets now contain composite lists of field names and properties (i.e. how the data in the fields is structured) that have been reviewed and revised to create one master list of field names. This master list will be used to create a final MS Access database into which all the existing records will be merged for further review.

Our to-do list for next week: